Writing Social Justice

Without making readers feel like they're being told what to think

Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940) opens with the novel’s protagonist Bigger Thomas killing a rat in his family’s one-room apartment. It’s not just any rat; it’s a foot-long, teeth-bearing monster of a rat that “could cut your throat.” Bigger has no choice but to kill it.

If this were a high school English class, we’d ruin the novel by discussing the scene’s “symbolism.” We’d set up an equation to the effect of rat = x and try to solve for x. In doing so, we’d reduce the novel and Wright’s brilliance.

True, the scene does predict how the novel plays out: Bigger, living in poverty in Chicago with no opportunity, could be said to be forced to kill the daughter of a white, rich family. Or is he? That’s the novel’s question.

Some say Wright defends Bigger’s crimes, excusing them as the result of systemic oppression, but what makes Native Son both a brilliant and successful social novel is that it doesn’t give any answers. It begs the questions, When is it justified to kill? When is the system solely to blame? The novel then attempts to answer those questions through the narrative.

The writer James Baldwin denounced the novel as polemical. Baldwin was a devout art-for-art’s-saker and saw Native Son and other novels as too neat and tidy. For him, they reinforce stereotypes rather than defying them.

I don’t agree with Baldwin—though I admire him as one of the greatest minds of the twentieth century—mainly because a polemic assumes that the writer intended to preach a cause. But as Wright explains in his essay “How Bigger Was Born,”

“[T]here are phases of Native Son which I shall make no attempt to account for. There are meanings in my book of which I was not aware until they literally spilled out upon the paper. I shall sketch the outline of how I consciously came into possession of the materials that went into Native Son, but there will be many things I shall omit, not because I want to, but simply because I don’t know them.”

If it wasn’t Wright’s intention to write a diatribe, can it be one?

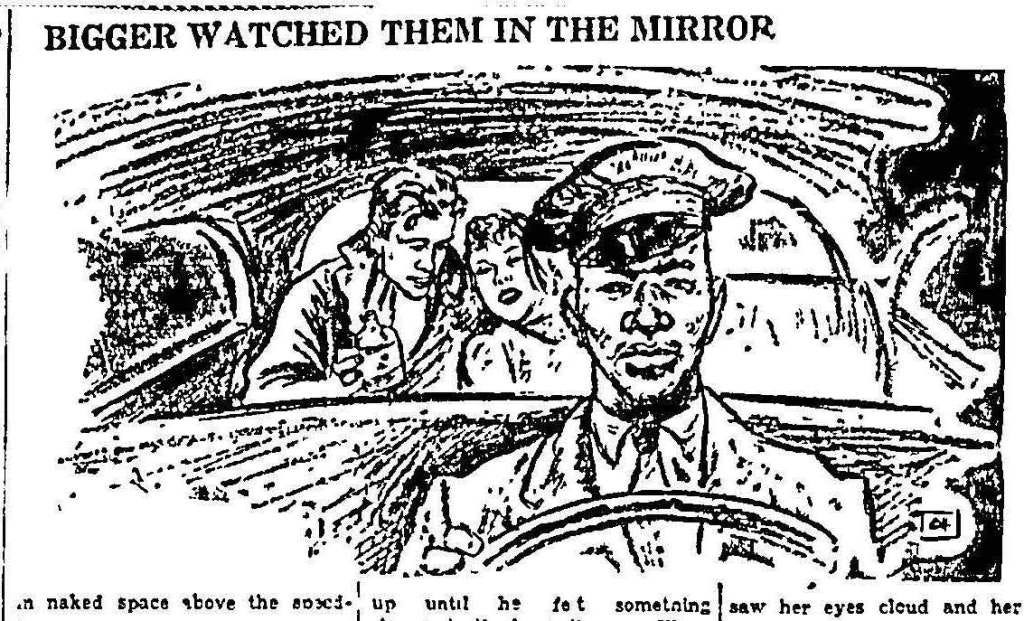

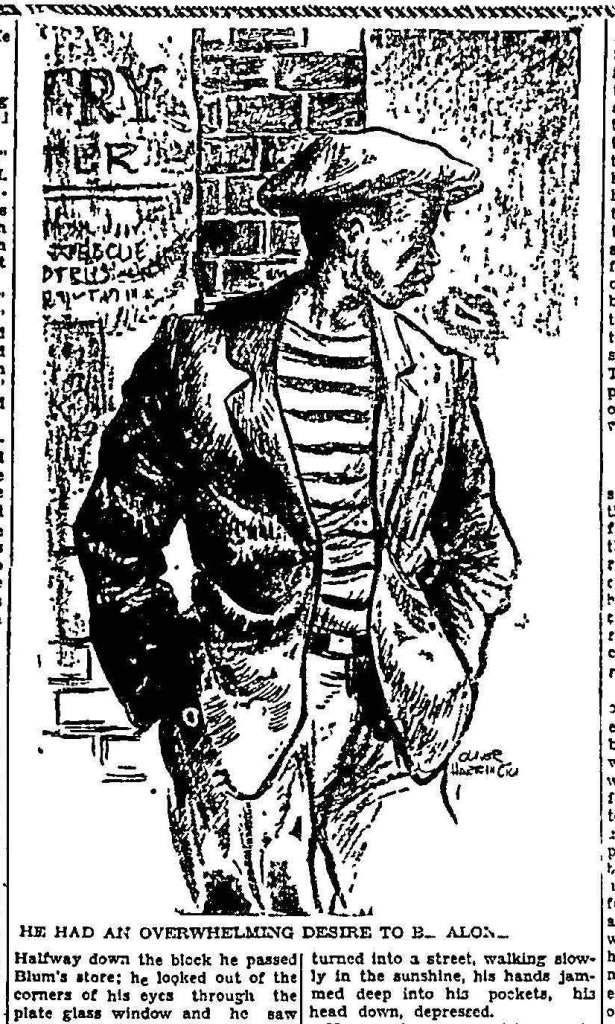

Native Son was partly serialized in two African American newspapers between 1941 and 1942 with illustrations by the groundbreaking cartoonist Oliver Harrington.

So how do you write a social novel or social justice memoir without being preachy? I’ve taught writing socially aware fiction and creative nonfiction to M.F.A. students for years. Below, I take you through the same prompts I give them.

If you aren’t yet a paid subscriber, become one. Your writing and writing career are worth it.

Prompt:

Choose a social, political, or economic issue. You can decide on it and then write or take a manuscript you think would benefit from having social justice as its primary or secondary concern and decide based on what you already have.

If you’re writing a memoir, when the term protagonist is used below, think of yourself as the protagonist.

Once you’ve chosen your issue, go through the following to hone it to make your fiction and creative nonfiction richer and more complex rather than reductive or simplistic. You don’t need to do all of them, just the ones that feel relevant to your project.

Start with a question, not an answer. That will allow you to work from the center of a dilemma than from an easy solution. Ask a question that makes you uncomfortable. For example, When is rape excusable? (Disclaimer: I’m in no way saying it is.) Ask an open-ended rather than a closed question: Not “Is killing the innocent ever justified?” but “When is killing the innocent justified?”

Once you’ve explored a social issue, ask it questions:

When it comes to abortion, when is it right to ________?

In a terrorist situation, when is it better to _______ than to____________?

Give your protagonist beliefs/standards/morals. Put her in a scene that will force her to confront the many dimensions of an issue. Play out all the possibilities.

Instead of using a cliché like love conquers all, let the story ask questions of it: What’s really more important—finding true love or saving one’s own life? When does love really conquer all? When doesn’t love conquer all?

Give your protagonist beliefs that matter, i.e., make them life or death, even if your protagonist is never in a life-or-death situation.

Reverse expectations. Take common assumptions and turn them on their heads.

Make your protagonist play devil’s advocate—have her wrestle with the issue.

Don’t give advice; instead, probe a dilemma, e.g., How would she forgive someone who has done the unthinkable to someone she loves?

Find two things that your character is dedicated to; make her choose between them.

Construct situations in which your protagonist’s equally strong convictions are in opposition to each other.

Look for ways to use her two desires to force her into doing something she doesn’t want to do. In other words,

bribe her (pay her to go against her beliefs) and/or

extort (threaten her unless she goes against them).

Force your protagonist to make a choice and act. Something that matters must be at stake. No easy solution, no easy way out. Your character must make a choice. That choice will deepen the tension and propel the story forward.

Force your protagonist to choose between two bad things. She must then live with the consequences of her decisions and actions.

Make your character reevaluate her beliefs, question her assumptions, and justify her choices. Ask yourself, “How is she going to get out of this? What will she have to give up (something precious) or take upon herself (something painful) in the process?”

Replace confusion and frustration with personalized Substack guidance—explore the Single Substack Strategy Intensive or Strategic Substack Growth Package.

A good reminder, too, of the importance of illustrations.

Working on it.